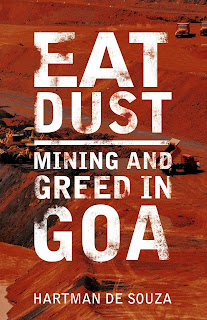

Hartman de Souza has blessed

those interested in Goa and its history with his must-read book, Eat Dust: Mining and Greed in Goa. It is

no easy task to write about the mining industry. One can easily get bogged down

by facts and figures, and thereby disengage the reader without painting the

bigger picture of what mining means beyond extracting elements from the earth. With

great expertise, de Souza weaves his narrative from a compelling blend of

memoir, travelogue, and investigative reportage, taking the reader on a guided

tour around Goa’s mines. This approach to the writing lends the human touch to this

subject that it so desperately needs, drawing the reader in right from page

one.

The book focuses in

particular on the ongoing battle between the villagers of Cawrem and mining

giant Fomento, featured regularly in the Goa news and kept in our consciousness

via social media through the work of the locals and their supporters throughout

the state and the diaspora. Importantly, Eat

Dust also offers a reality check to those who still believe Special Status

is in the cards—or ever really was—for Goa.

de Souza’s ability to vividly

describe even the most grotesque and tragic images of Goa’s destruction will

keep the reader turning the pages with wonder at what he has to say next. Take,

for example, the following: “When they were done pumping the water out, there

was still a small amount left in the pit. That water would, like a festering

sore turn rancid and green with slime after a few days in the sun” (p. 18).

In de Souza’s impeccable

writing, one cannot help but be drawn in by his palpable love for Goa. The

frustration that can only come from such a deeply personal connection reaches a

climax in the following account of his choice to run away to Pune as operations

were about to accelerate in Maina and Cawrem:

I wanted to speak for the earth’s injured

voice, but needed to run away from my own notes and the pictures in my mind. By

early August 2008, they were beginning to eat circles in my head. I could even

see them in my sleep. Those days, I felt like swinging at anyone who even

suggested that the greed could be halted with our tactics and strategies. (p.

140)

Also commendable is the

author’s boldness in spotlighting individuals who have either contributed

directly to promoting the interests of the mining industry or who have shown

the kind of preference for greed over ethics that has helped fuel the rampant

apathy toward the obliteration of the environment. de Souza is not afraid to

name names!

There is no greater time than

the present to read this book. The title itself is indicative of the present

state of Goa. On a recent trip to the state, I was struck by the number of

people who now ride their scooter or motorcycle with their face covered, and

the chorus of coughs I heard during mass. I, too, found myself inhaling dust

while travelling short distances around North Goa. Perhaps we are all choking

on development!

My only criticism of Eat Dust is an editorial one. Much of the

material in the ‘Afterword’ is as essential to the text as the chapters that

precede it, particularly the takedown of trickle-down economics. Just as the

foreword is given the title ‘A Bird’s Eye View’, integrating it into the text

(because some readers will skip right to Chapter One), this should have been

accorded a descriptive title to clarify that its contents are integral to the

larger text.

Nevertheless, Eat Dust engages and leaves the reader

thinking about the future of Goa. What more can one ask of a book?