When I was an adolescent and young

adult, I consumed any LGBTQ content I could find. In particular, I watched a

lot of movies that fell into that genre—most of them incredibly bad. There were

some nice stories centred around men, though. My favourite remains E. M.

Forster’s novel Maurice (also adapted into a beautiful Merchant Ivory film in

1987).

Another old favourite is the film Love! Valour! Compassion! (adapted in 1997 from the 1994 play). And finally,

there is The Wedding

Banquet (1993)—one

of the few narratives I can remember that wasn’t entirely about white people.

There were also The Crying

Game (1992) and Boys Don’t

Cry (1999) that helped initiate

a conversation (albeit a transphobic one) admitting that transgender people

exist.

The tales about queer women, however,

were a little less enticing. Movies like Salmonberries (1991), whose only saving grace was the song “Barefoot,” Lost and

Delirious (2001), and

But I’m a

Cheerleader (1999), I

found unrelatable and generally boring. Even Bound (1996), which I admittedly watched repeatedly, wasn’t

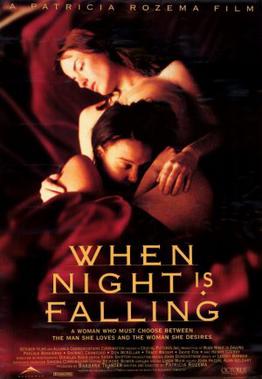

a particularly well-written script or tremendously acted film. But there was When Night Is

Falling (1995),

which did a far better job than any other movie at the time of dealing with the

complexities of sexuality and identity. Where it really failed for me was in

its faithful adherence to the melodramatic standard of films about queer love,

similar to Brokeback

Mountain (2005).

Many such stories have been either

tragic (NB: Desert Hearts [1985], another snoozefest, was recognized as the

first “lesbian” film where no one died in the end) or homonormative (e.g., The Kids Are All Right [2010] and If These Walls Could Talk 2 [2000])—that is, projecting the idea of a model

queerness resembling heterosexuality, where life is depicted as a journey of falling

in love, getting married, finding a sperm donor, raising a family, and enjoying

a largely sexless existence. This is not what real life looks like for the vast

majority of the queer people throughout the world—many of whom are still

fighting for their very survival.

By the time the highly critically

acclaimed Carol was released late last year, I had given up on the

LGBTQ genre. I was tired of seeing the seemingly endless longing looks across

the room, the tears, the infidelity to the opposite-sex partner or spouse, the

sometimes awkward kissing scenes, the lack of sex (thank goodness for the TV

series Queer As Folk [2000–2005], in that respect, despite its shortcomings),

and the death. But I told myself I should see it before judging. So, I watched Carol—and sadly, it didn’t disappoint!

I’m not sure what the critics found so spellbinding about it. In a word, it was

excruciating.

First, the pace of Carol is tremendously slow. From the first scene, nothing much

happens besides the introduction to the intimate relationship between Carol and

Therese. We see a lingering touch. This is followed by a flashback to the first

time the characters meet—a scene replete with those aforementioned longing

looks. Carol is in a department store, where Therese works, shopping for a

Christmas gift for her daughter. She goes to Therese’s counter seeking advice

on what to purchase. This exchange sets up the class division between the two

characters and also sheds light on Therese’s nonconformity to gender norms

(e.g., she preferred trains to dolls as a child). After paying for an

expensive, hand-made train set, Carol leaves her gloves behind, thus giving

Therese an excuse to refer to the sales receipt and retrieve her customer’s address.

After this, however, there is no real build-up to the development of the relationship

between the two protagonists. Therese just enters Carol’s upper class world and

starts spending time with her both in her home and out in public. The

transition appears seamless, even though Therese is never depicted as someone

who desires to ascend the social hierarchy. What we do know about her is that

she wants to be a photographer. Even there, I didn’t sense any real passion for

this art form. The character development in the film is just not there.

The film also fails to provide insight

into how these two characters actually reach the point of loving each other.

The dialogue is not particularly engaging for the viewer. I was so bored

listening to them, I can’t remember anything poignant to suggest that any

attraction grows from intense conversation or finding shared interests. In that

respect, this movie reminded me of Brokeback

Mountain, where the audience was just supposed to buy into the love story

because we were told there was one, not because we actually watched love unfold

between Jack and Ennis.

Also highly disappointing is that there

is very little made of the important issues raised in the film, such as class,

as I mentioned, and divorce and child

custody, patriarchy, and homophobia. One of the main conflicts in

the film is that Carol and her husband are going through a messy divorce and he

is seeking full custody of their daughter. The significance of this part of the

plot, however, seems to be forgotten toward the end. Given the era (the 1950s),

where divorce was rare, especially on the grounds of adultery with someone of

the same sex and a father pursuing child custody, one would expect more to be

made of this. It was as if the director forgot the story wasn’t set in the

twenty-first century. Further, there is no exploration of why this particular

extramarital relationship with Therese pushes Carol’s husband over the edge,

when he has already accused his wife of having been unfaithful in the past and

has wanted to stay with her anyway.

Finally, despite portraying Carol as an

experienced, almost predatory, woman, there are no kissing or love scenes until

an hour and fifteen minutes into the film! Yes, I can pinpoint because I got

fed up listening to the blah blah blah and

seeing those drawn-out looks and forwarded! I was so exasperated with the movie

that I said, “If nothing’s happening, at least there should be a hot sex scene!”

It isn’t that hot, by the way. In fact, it is slightly bizarre. This is where,

I would argue, Cate Blanchett distances herself from her character; she looks

slightly uncomfortable kissing Rooney Mara, and then suddenly, she is like a

fish to water when she simulates oral sex. Perhaps this was intentional; if

Carol is the promiscuous woman her jealous husband insinuates she is, perhaps

she is more accustomed to performing other acts and less comfortable with the

intimacy of kissing. However, given that the rest of the film lacks nuance, I

doubt this is deliberate. It is also important to note—without giving away too

much—that this scene serves a particular purpose to move the plot along; it is

not, in fact, the climax of all the melodrama leading up to this point.

All in all, Carol is the same old formulaic, unrelatable, excessively white, boring

story we must all be accustomed to. I want more, and I expect better. I think

the only way this might happen is if I write my own screenplay.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.